Pharma companies are legally required to test novel drugs in animal models before beginning human trials. And while animal testing has progressed thousands of therapeutics that we use today, it is not without its experimental and ethical downfalls. An article published in the Financial Times described how scientists are moving away from animal experimentation toward alternatives that more closely resemble human physiology.1 The piece, titled "How science is getting closer to a world without animal testing", explores the complicated relationship between drug development and animal research, and lists some of the alternatives that are being used in laboratories today.

This article focused primarily on microphysiological systems (MPS), like organ-on-a-chip, yet there are many more experimental models being used to replace animal research during late-stage drug development. Some examples include in silico techniques, which employ computational and machine learning (ML) methods, and ex vivo assays, which use living tissues to determine drug behavior. While the latter, also known as human tissue testing, is not well recognized, it could provide equally (or more) translational results depending on the experimental end-point.

If you are not familiar with ex vivo assays, these experimental models use donated human tissues to test the efficacy and safety of drugs. While organ-on-a-chip technologies can explore the effect of drugs on multiple organs simultaneously, ex vivo studies have a physiological complexity that cannot (yet) be replicated by man-made systems. These living models have been critical in the progression of several compounds in late-stage development, four of which we have listed below.

1. Ex vivo models provide proof of concept in human tissues

Arcede Pharma, a spin-out from Respiratorius (Lund, Sweden), used an ex vivo study to assess the ability of RCD405 to relax healthy human, rat, and canine airways. In all species, including humans, the candidate drug produced concentration-dependent relaxation of the airways comparable to internal reference compounds and standard-of-care therapies for COPD and asthma. These data will form part of RCD405's submission to the regulatory authorities in advance of clinical trials and represents a useful commercial milestone by demonstrating proof of concept in human tissues.

[READ MORE] How human fresh tissue models are helping RCD405 achieve regulatory approval →

“These are crucial important results for RCD405 where, for the first time in the same model, we can compare with established bronchodilatory substances. Something that was also requested earlier at the scientific advisory meeting at the Swedish Medical Products Agency.”

– Johan Drott, CEO, Respiratorius

2. Ex vivo models avoid species differences

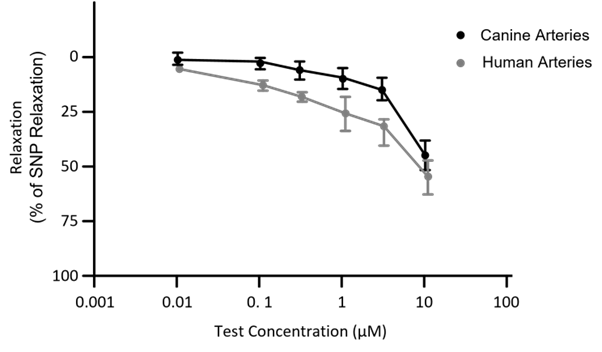

When cancer treatment AMG337 started causing headaches in clinical trial participants, researchers went back to the lab to determine why. They compared the effects of the treatment on canine blood vessels (used in preclinical studies) to human blood vessels, discovering that canine studies underestimated the impact of the drug on humans. Human fresh arteries gave a more accurate estimate as seen in figure 1 below, reflecting the possibility that the compound might cause vasodilation of blood vessels that could explain the headaches. As a result of these and other experiments, the company was able to devise a strategy to safely mitigate any adverse effects and continue the development path.

[READ MORE] Human tissue testing rescued Pharma's drug from clinical failure →

Figure 1: Relaxation response to AMG 337 (shown as % relaxation) in pre-constricted canine and human blood vessels.

Figure 1: Relaxation response to AMG 337 (shown as % relaxation) in pre-constricted canine and human blood vessels.

3. Ex vivo models generate human data to support regulatory submissions

The International Partnership for Microbicides (IPM) has developed an HIV prevention product using the anti-retroviral drug Dapivirine. This intravaginal ring is designed to be self-inserted without the assistance of a healthcare professional, providing an extra tool for the prevention of HIV in high-risk areas. When the European Medicines Agency (EMA) requested investigations into the potential effects of the intravaginal ring on the uterus, IPM conducted studies on human fresh uterine tissue measuring the effects on uterine contractility. No effect was observed ex vivo, and the ring subsequently received a positive opinion from the EMA in 2020 and approval by the WHO in 2021.

[READ MORE] Everything you need to know about the Dapivirine Vaginal Ring for HIV prevention →

“[These] unique capabilities enabled us to generate important data on the safety of the Dapivirine Vaginal Ring for women’s HIV prevention.”

– Jeremy Nuttall, IPM

4. Ex vivo models can troubleshoot adverse effects

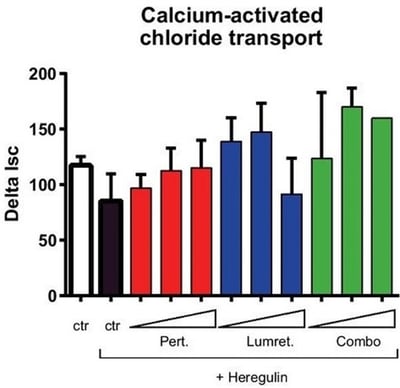

When a combination therapeutic was causing diarrhea in some clinical trial participants, Pharma used human intestinal tissue to help uncover the mechanism. Ex vivo studies in an Ussing Chamber revealed that an up-regulation of chloride channels was responsible for this adverse effect seen in patients (figure 2). To combat this side effect, the clinical researchers prescribed chloride channel blockers to subjects experiencing diarrhea, meaning the clinical trials could continue.

[READ MORE] Human tissue testing helped Pharma reduce diarrheal toxicity →

Figure 2: Ex vivo assessment of ion transport in fresh intact colonic mucosa allowed various combinations of drugs and concentrations to be tested.

Figure 2: Ex vivo assessment of ion transport in fresh intact colonic mucosa allowed various combinations of drugs and concentrations to be tested.

The future of animal testing

It is likely that it will take decades for Pharma's dependence on animal models to subside. Researchers have relied on the same animal systems for hundreds of years, which means there is a vast amount of data supporting their use. To eliminate animal testing completely, we require more advanced technologies and more data from current non-animal alternatives that accurately estimate clinical safety and efficacy. By using and developing new in silico, ex vivo, and MPS models, researchers can increase the proportion of non-animal data and encourage regulators to reduce their dependence on in vivo data as the gold standard of preclinical research.

References

- Cookson et al. How science is getting closer to a world without animal testing. The Financial Times (2022)