From obesity and Crohn’s disease to cancer, investigations into the microbiota and microbiome are opening up numerous avenues of research. The human microbiota, composed of microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, eukaryotic microbes, and many different species which occupy the human body, and the study of the associated microbial genomes, are generating increasing numbers of publications.

The microbiome and malignant melanoma

Dr Jennifer Wargo (Associate Professor, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Centre), in a recent publication in 2016, examined fecal samples from patients with advanced malignant melanoma who were treated with an anti-PD1 therapy that blocks the PD1 protein on T-cells. Her study isolated two bacteria that help buoy PD-1 immunotherapy response in metastatic melanoma.

After treatment, the microbiome from ‘responders’ and ‘non-responders’ was profiled with genetic sequencing, and the findings showed major differences both in the diversity and composition of the gut microbiome between the ‘responders’ and ‘non-responders’. A greater bacterial diversity was present in the gut of the responders compared to the non-responders. Furthermore, when fecal microbes from ‘responding’ and ‘non-responding patients were transplanted into germ-free mice, the mice that received transplants from responding patients had significantly reduced tumor growth, higher densities of beneficial T-cells, and lower levels of immune suppressive cells.

Thus, this brings forth the hypothesis that by examining the microbiome, can we predict patient responses to drugs and therapies and ultimately treat diseases such as cancer more effectively?

Can we predict patient responses to drugs and therapies and ultimately treat diseases such as cancer more effectively?

The microbiome and colorectal cancer

Another recent publication in 2017, by Dr Libusha Kelly (Assistant Professor, at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York) and colleagues investigated whether the composition of a person’s microbiome influenced whether Irinotecan (a chemotherapy drug used to treat colorectal cancer, which is activated into its toxic form in some people by digestive-tract bacteria causing serious side-effects), would be reactivated or not.

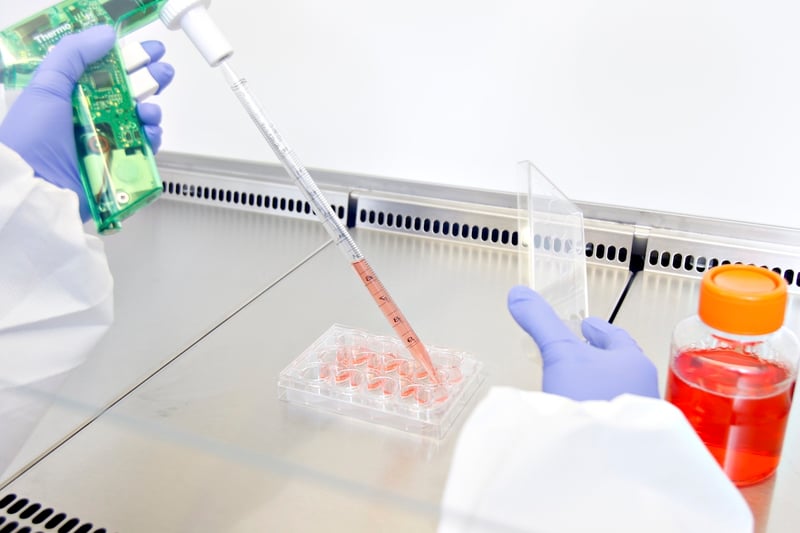

The researchers collected 20 fecal samples from 20 healthy individuals and treated them with inactivated Irinotecan. Using metabolomics, four of the 20 individuals were found to be “high metabolizers” and the remaining 16 were “low metabolizers”. The fecal samples of both groups were analyzed for differences in the composition of their microbiomes, focusing on the presence of the enzyme beta-glucuronidase; the digestive-tract enzyme which reactivates Irinotecan. Significantly higher levels of this enzyme were reported in “high metabolizers” compared to the “low metabolizers”. It was hypothesized that those who are “high metabolizers” would be at increased risk for side effects if given Irinotecan.

Lastly, the study concluded that by analyzing the composition of patient’s microbiomes before giving Irinotecan it could be possible to predict whether patients would suffer the side effects. In addition, a mouse study in 2010, suggested it may be possible to prevent adverse reactions by using drugs to inhibit specific beta-glucuronidases.

Summary

It is most likely that the microbiome will become the next hot topic and a major battleground in our search for new drug therapies, especially within cancer research. Understanding the effects of microbes on the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of drugs would take us a step closer to effectively treating patients, with reduced side effects.

References

- Cancer Research UK. The microbiome and cancer: what’s all the fuss about? (2017)

- Meghana Keshavan. The bacteria in your gut could help determine if a cancer therapy will work. STAT (2017)

- News Release. Bacteria in the gut modulates response to immunotherapy in melanoma. MD Anderson Cancer Center (2017)

- Greener. The microbiome: a gut feeling about drug metabolism. Prescriber (2018)

- Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Gut Microbiome May Make Chemo Drug Toxic to Patients (2017)

.jpg?width=1000&height=562&name=Untitled%20design%20(10).jpg)